Project Overview

Welcome!

This page introduces the activities of the 2019 Toyota Foundation International Grant Program project “Vitality-Producing Entrepreneurship, Advocacy, and Research with an Eye to Aging and the Movement of People in Asia: Interactions between Ex-EPA Nurses from the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam.”

Nurses from Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam come to Japan under economic partnership agreement (EPA) frameworks every year. To become registered nurses in Japan, they study Japanese and prepare for the national nursing exam while receiving on-the-job training at their respective host hospitals. If they pass the national exam, they work as registered nurses, but if not, they, unfortunately, have to return home. Some pass but choose to go home for various reasons. With the support of the Toyota Foundation, we are carrying out a project that focuses on EPA nurses who have returned to their home countries.

Project Representative: Michiyo Yoneno-Reyes (University of Shizuoka Professor)

Project Co-Representative: Yuko Hirano (Nagasaki University Professor)

About the Project

Since 2008, more than six thousand nursing and care personnel have come to Japan under the country’s economic partnership agreements (EPAs) with Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. About half of them have already returned to their home countries. Having learned the Japanese language, as well as geriatric nursing and caregiving skills, in Japan, after returning home, they have the potential to create solutions for the aging of society and the exodus of nursing and care personnel, problems faced by not only Japan but their home countries as well. This project considers what can be done to provide logistical support for former EPA nursing and care personnel engaging in innovative practices, research, and entrepreneurship.

In this project, returnees gather at workshops to introduce the unique activities of these three countries. Examples include the establishment of the “nurse social worker” profession for returnee nurses who have learned how to provide comprehensive care for older adults; educating people about health promotion that incorporates Japanese oral swallowing care; and social entrepreneurship for returnees preparing to retake the national examination while working to save up the funds for doing so. While the sending countries are suffering from brain drain due to excellent nurses going to Japan, we hope to create opportunities for these returnees to put their skills and knowledge to use and flourish.

Foreign Nurses Coming to Japan Under the EPA System

It began with the aim of promoting bilateral trade

Japan and its trading partners bilaterally conclude economic partnership agreements (EPAs) to make trade go more smoothly. The Japanese government has taken the stance that the acceptance of nurses based on the EPA system “is not a response to the labor shortage in the nursing and care sectors, but is implemented to strengthen economic cooperation as a result of negotiations based on strong requests from partner countries” (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare). Foreign nurses are accepted under EPAs signed with the Philippines (2006), Indonesia (2007), and Vietnam (2009; Memorandum in 2011).

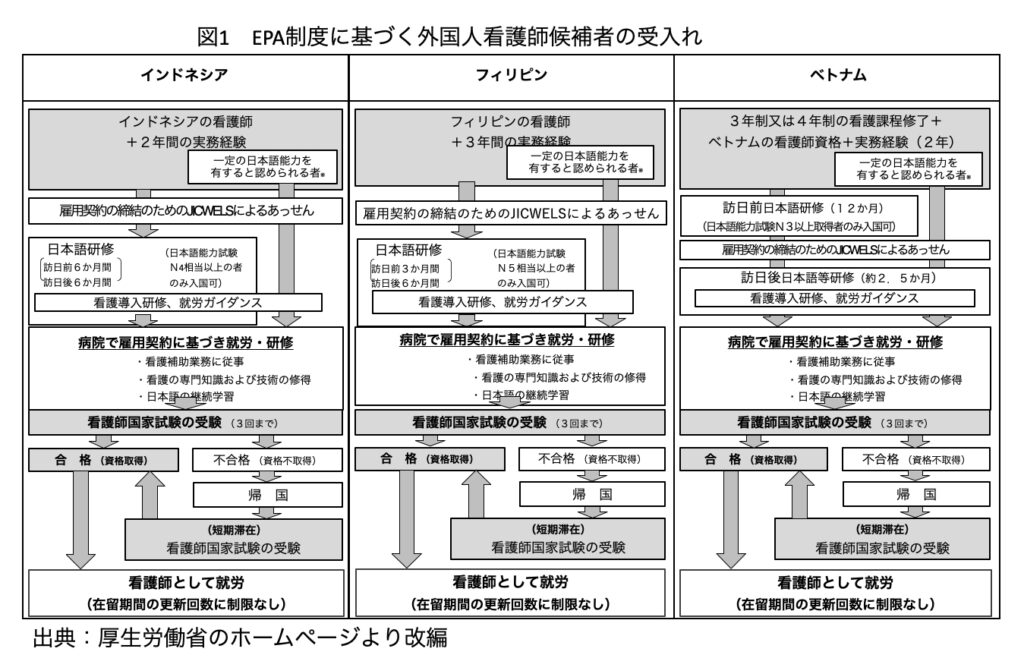

How nurses come to Japan under the EPA system

To work as a nurse in Japan, one must pass the national nursing examination in Japanese. Therefore, foreign nurses must acquire Japanese language skills. However, under the EPA system, the length of the Japanese-language training period before coming to Japan and the Japanese language requirements at time of entry differ from country to country. Also, the training and support prior to becoming a nurse currently varies from hospital to hospital. As a result, many foreign nurses are forced to return to their home countries because they cannot pass the national examination in Japanese, even though they are adept professionals.

The EPA nurses

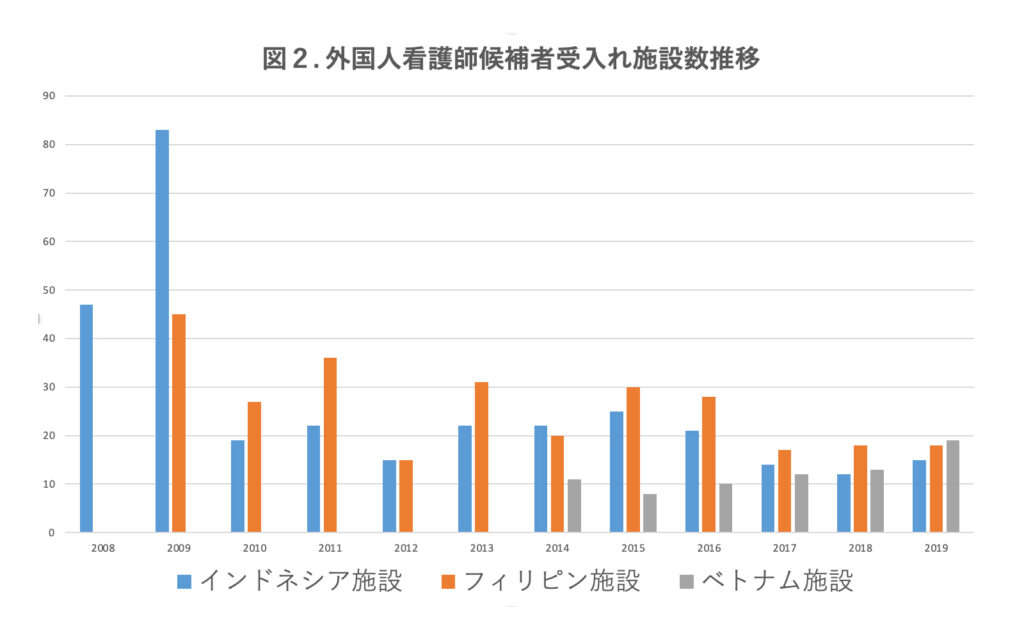

As of 1 March 2021, the number of foreign nurses that have come to Japan based on EPAs is as follows: 714 from Indonesia (since 2008), 588 from the Philippines (since 2009), and 180 from Vietnam (since 2014).

At first, there were a lot of job openings and job seekers, but recently, these numbers have leveled off. Also, the number of job openings for Vietnamese nurses is rapidly increasing compared to Indonesia and the Philippines (see Figure 2, based on materials from Japan International Corporation of Welfare Services/JICWELS).

Problems in accepting foreign nurses under the EPA system

Behind the slowdown in the number of accepted foreign nurses are the system’s design problems. For example, in some countries, pre-assignment training is inadequate, making it difficult to work in a clinical setting or study effectively for the national exam once in Japan. It is estimated that the additional cost (excluding salary, bonuses, social insurance, etc.) for a host hospital to have one EPA nurse successfully pass the national exam is 2.02 million yen (Tsubota, p. 174). This is in addition to other burdens that cannot be converted into monetary amounts, such as support and accommodations for life in Japan. In this way, it is not easy for the host hospital to hire foreign nurses.

On the other hand, foreign nurses have also voiced their concerns about the inequality of the national examination support system, which differs from hospital to hospital. In this way, even if they want to work as a nurse in Japan, it is difficult under the EPA system because the national examination barrier is too high.

The decrease in job openings and job seekers appears to be a manifestation of the above problems. It seems that recently, more and more hospitals have been shifting to bringing in Chinese nurses and others outside the EPA system.

Is the EPA system suited for bringing nurses to Japan?

Why do these problems occur? As mentioned earlier, the EPA system was established to promote trade, so Japan prioritizes the likes of car exports and liquefied natural gas imports. It must deal with nursing-related aspects while working on running this system.

In the first place, nurses are human beings, professionals who can decide where to work at their own will, so they are not suited to be bartered for things. On the other hand, when operating the EPA system, there is the diplomatic consideration of not making the partner country look bad, and therefore certain issues, such as the need to secure a certain number of nurses, must be addressed. It appears that for these reasons, it is difficult to efficiently operate a system that reflects the wishes of foreign nurses themselves and the host hospitals.

How to bring in foreign nurses in the future

The Japanese government’s stance is that it will not stop accepting nurses under the current EPA system unless requested by the sending country. However, currently, things are dependent on the foreign nurses and host hospitals’ efforts.

We want to propose measures that will make the national examination less of a barrier, even if only a little bit, not only for foreign nurses currently in Japan, but also for those who have returned home. Also, for those who have no choice but to return to their home countries, we would like to find a way for their work experience in Japan to be useful in some way for Asian countries. (24/10/2021, written by Yuko Hirano)